I recently visited the University of Maryland

to give a colloquium

(slides here).

This was my first in-person colloquium as faculty because of COVID.

I had a great meeting with the grad students over lunch, and they asked several good

questions. I've thought over some of them a little more and wanted to fill out my answers.

I'll paraphrase two questions:

"How do you balance coding work with other research work?"

My answer was essentially, "All of my coding work is research work - I don't write

code that doesn't contribute to my research." That is broadly true, but not exclusively

so, and there are some exceptions.

All of the coding work I have done has been either to enable my research, support

someone else's research, enable my research career, or (in theory) make my life easier.

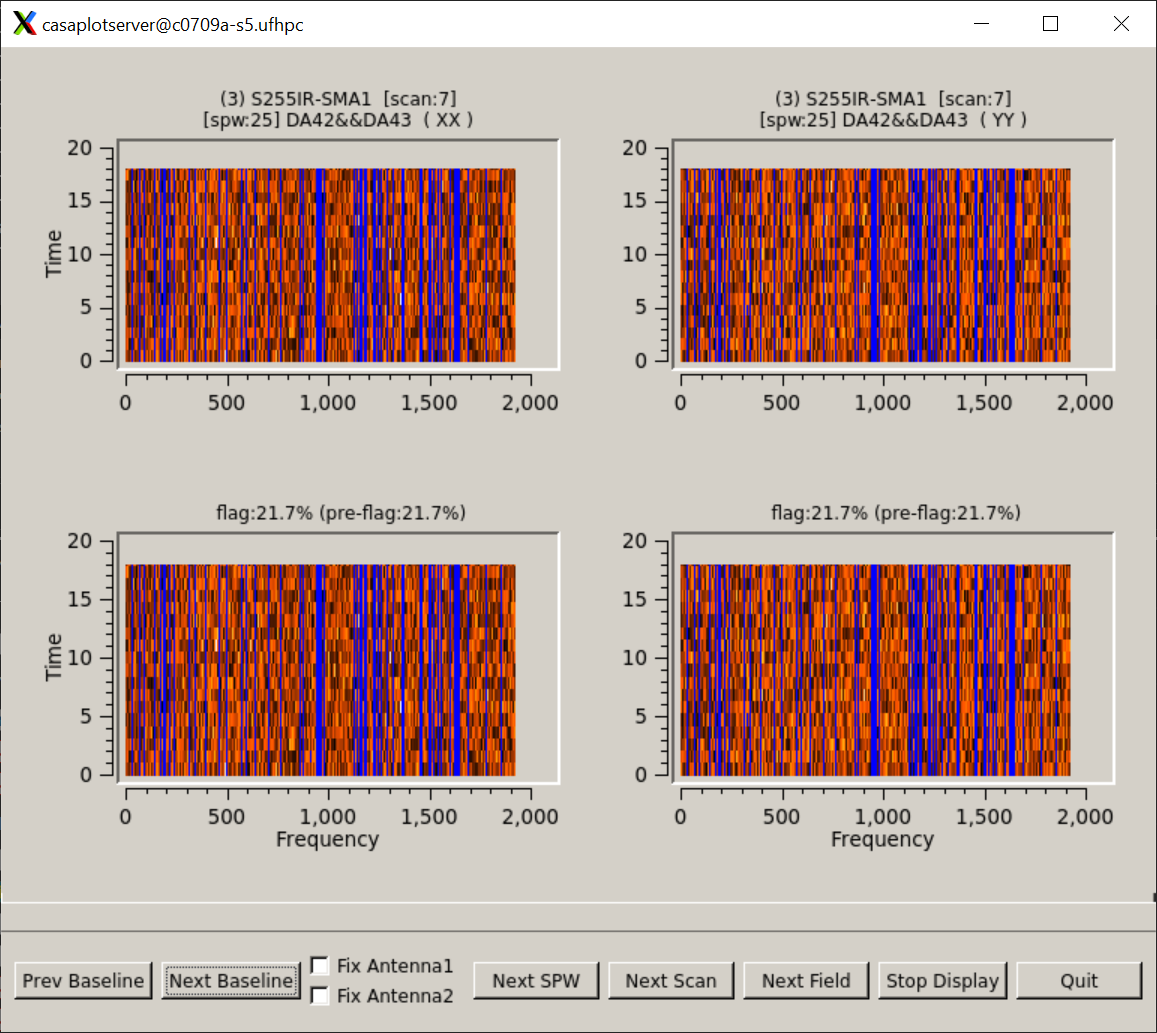

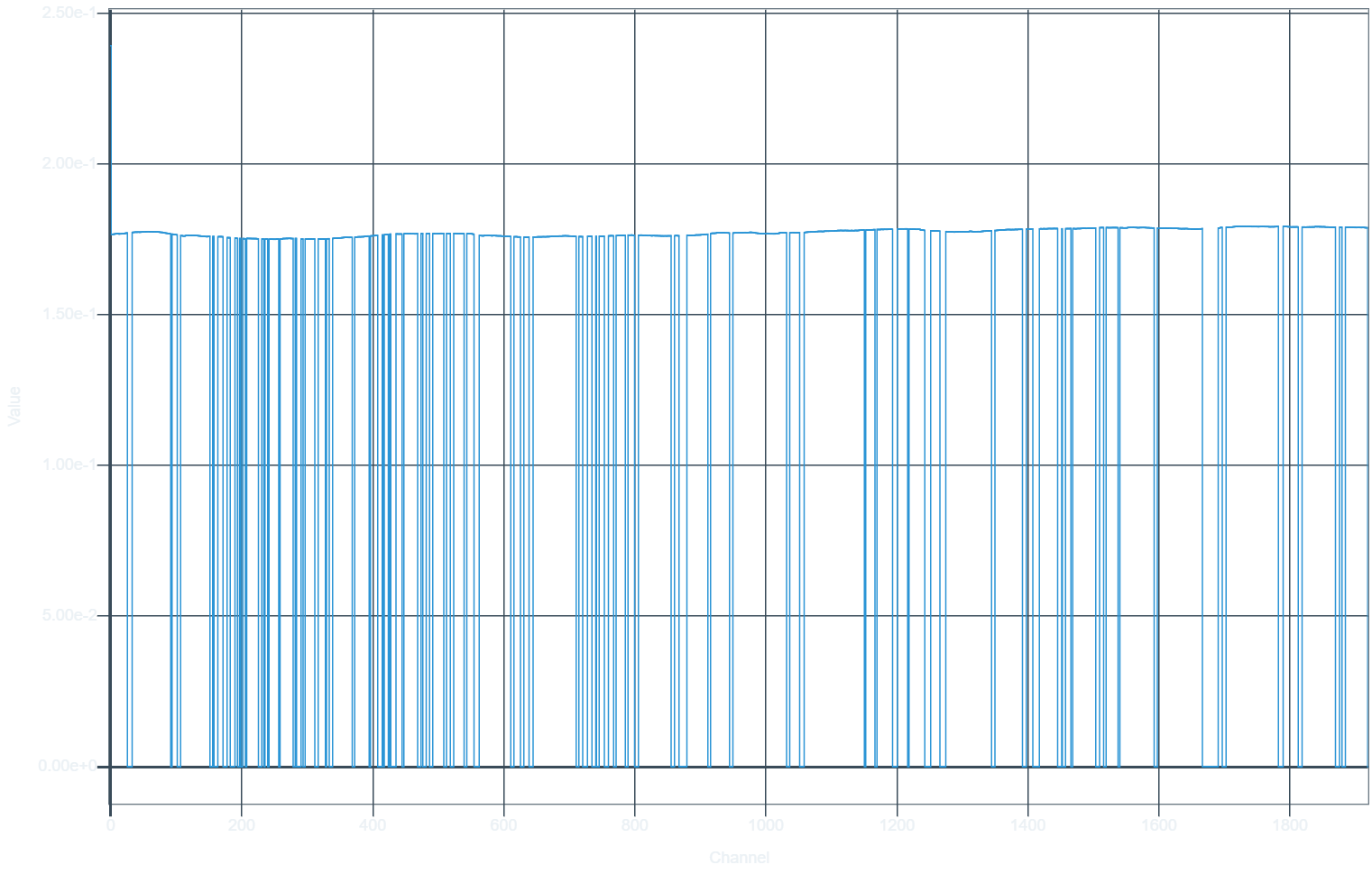

The research stuff is mostly obvious - my work on and with data reduction software

(see all the CASA-tagged blog posts here, all development on radio-astro-tools, etc),

pyspeckit, and most of astroquery. On the astroquery side, a lot of my research work

wasn't directly going to papers, but was instead to dig through the archives to see

if data were available, or if I needed to obtain new data. It was then useful

for supporting observing proposal writing.

The "enable my research career" component included a lot of side-work on things

that aren't directly research, but are research-adjacent. These projects

included building tools to deploy my papers to github (which was a bit

obsoleted by overleaf), automatically updating reference lists (it turns

out I often cite 5-10 arXiv papers in an article, but by publication time, I

need to update them to official journal article citations), assemble lists of

coauthors, add citation counts to the CV, writing this

blog, etc.

The exceptions are some of the 'pure service' coding. This necessarily had to

be the lowest priority most of the time, but this is still career-motivated.

Some of the contributions I've made to astropy & other open-source projects are

just to improve their code bases, either with bugfixes, added features, or

things to improve robustness. Most of my contributions were directly motivated

by need, of course - either there was something basic missing, or I was the

expert in that particular subtopic. A good example is the J-to-K equivalency;

it wasn't directly research-motivated, but was something I found myself needing

in day-to-day work.

The 'pure service' coding also entails maintaining projects. There is still a

selfish motivation here: if the code is maintained (if other people are using

iti and finding bugs), it is more likely to be functional when I need it next.

But, most of this work isn't triggered by my own needs, but by others.

The astropy Moore grant now funds some of this work, which helps ensure that

I'm motivated to continue the maintenance - but I was doing a lot of this work

as a postdoc long before I could be directly paid for it.

"How do you avoid being typecast as a coder?"

This question came from students who got to be known in their research

collaborations as "good at coding". My answer was basically, "learn to say

no", but there's more nuance to add.

First, there are some solid career paths to follow by being the science coder

in a group. Many observatory jobs, for example, would prioritize this coding

experience. There are a lot of positions in observatory jobs at places

like STSCI, NRAO, NOAO, etc. that value this sort of skill over many others.

So if you want to pursue one of these paths, or an industry path, because

you <i> enjoy </i> the coding, then great! Do it!

If you really enjoy the coding, you'll get to do a lot more of it in a job

focused on software development than in an R1 research job.

That said, if you are interested in pursuing an R1 faculty job, you need to

strike a more careful balance. It's fine if you're the coder in the group -

that can land you a coauthorship on a lot of papers, which is a good thing!

However, first and foremost, you need to publish your own (first-author)

papers, which means prioritizing your work over collaborative work. Ideally,

you'd just do both - that's what's expected of faculty members (faculty members

can't choose to prioritize teaching or research, really - they have to do well

at both, which often means just putting in more hours). But if you're faced

with the choice, a few first-author papers are more important than many

co-author papers.

The way I struck the balance was to focus entirely on research papers during my

grad school career, but still do a lot of software support work on the side - I

put in more time, but it was all stuff that was useful both for me and for

collaborators. Later, in my second postdoc, I started publishing code-only

papers; I would advise grad students to do this sooner, though. Since AAS

journals now accept code papers, if you want coding to be a big part of your

research portfolio, it's a good idea to have a refereed paper on a piece of

software. Note that some of the most highly-cited papers in astronomy are code

papers, like the DAOPHOT, SEXTRACTOR, and astropy papers.

Last bit of advice closing this out: Avoid GUI development. That way lays madness.